THE HAUNT & THE TAUNT

Effective leadership is distinguished not by how often it blames predecessors, but by how decisively it corrects course. That can be done without rhetorical mudslinging that stains even borrowed garments

THE HAUNT & THE TAUNT

When delivery is questioned, history becomes a straitjacket. It is a taunt, yes — but it is also a caution. None of this is to deny that Jawaharlal Nehru made mistakes. He did. So did Indira Gandhi. So did Rajiv Gandhi. But no prime minister, past or present, is infallible; Narendra Modi, Morarji Desai and Atal Bihari Vajpayee were no exceptions. Acknowledging historical missteps need not weaken the present; it can strengthen it

“A dream has been shattered, a song has been silenced, a flame has vanished into the infinite. It was a flame that burned through the night, fought every darkness, and showed us the way.” — Atal Bihari Vajpayee, homage to Jawaharlal Nehru, Lok Sabha, May 1964.

There is a curious habit that has embedded itself in India’s political monologue over the past decade. As questions sharpen, responses blur. As scrutiny tightens, the debate retreats into history. And when responsibility looms, the argument quietly reverses direction.

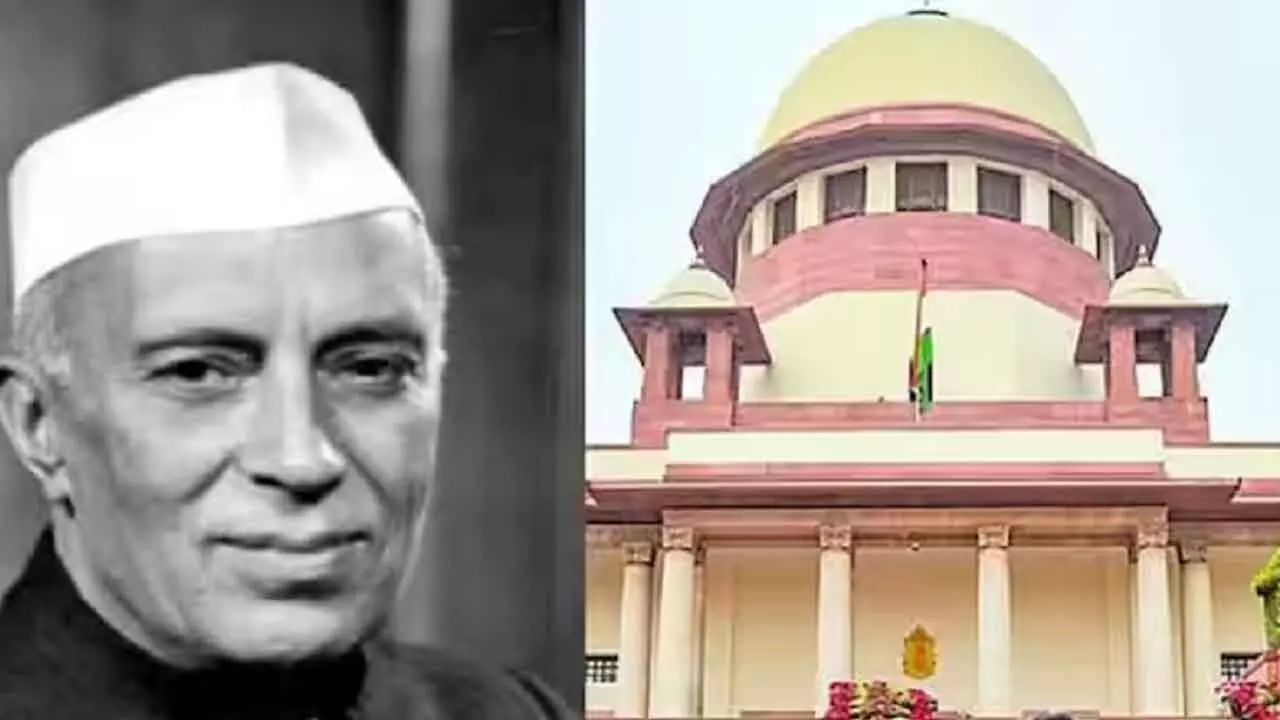

That history is almost always compressed into a single name: Jawaharlal Nehru.

More than sixty years after his death, India’s first Prime Minister continues to loom large in present-day political rhetoric. Not as a figure to be evaluated with proportion and context, but as a ready-made explanation for problems that persist in the here and now. From the floor of Parliament to local election platforms, Nehru’s name returns with striking predictability. Not reflection, but reflex.

Over the past eleven years, Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Home Minister Amit Shah, cabinet colleagues and senior BJP leaders have repeatedly invoked Jawaharlal Nehru — almost invariably in a negative register — across debates ranging from China and Kashmir to public sector enterprises, foreign policy, federalism and institutional architecture.

The frequency of these references has become so notable that it has drawn formal remark within the Lok Sabha itself.

During a recent parliamentary exchange, Congress deputy leader Gaurav Gogoi observed that the Prime Minister had mentioned Jawaharlal Nehru more than two dozen times in a single debate, asking whether the House was examining present-day governance challenges or prosecuting an argument with a leader long deceased. The point was not numerical precision, but emphasis — and it resonated.

The pattern is telling, and it is intentional. When outcomes disappoint, responsibility is routinely relocated to the past. In corporate language, it resembles leadership that continues to fault inherited systems long after assuming full control. Eventually, even patient stakeholders lose interest.

India today is not the India of 1947, nor of 1962, nor even of 1991. It is the world’s fifth-largest economy, enmeshed in global capital, supply chains and strategic partnerships. It seeks to emerge as a manufacturing base, a digital power and a consequential geopolitical actor. Crucially, it is also a country governed by the same political leadership for more than a decade.

At some point, inheritance must give way to ownership. That is why Priyanka Gandhi Vadra’s recent intervention merits attention beyond party lines. Her challenge was neither nostalgic nor defensive. It was direct. If Jawaharlal Nehru, Indira Gandhi and Rajiv Gandhi committed strategic, political or economic errors, let those be examined fully, debated honestly and concluded definitively. Place the record on the table, close the chapter, and turn squarely to the problems of the present.

Enough governance by rear-view mirror. Her argument found traction because it articulated a weariness many Indians recognise — the sense that grievance has displaced governance as the dominant political language. Stop lamenting. Start governing.

India confronts persistent challenges: employment shortfalls, rising living costs, uneven income distribution, stress among small and medium enterprises, and growing concern about institutional autonomy. These are not ideological constructs or opposition inventions; they shape consumption, investment confidence, social cohesion and long-term growth prospects.

Yet instead of sustained engagement with these realities, the national conversation repeatedly loops back to the early decades after Independence.

Why? Because grievance politics demands less effort than performance politics.

The narrative follows a familiar script. When employment data disappoints, Nehru’s economic thinking is faulted. When China acts aggressively today, diplomacy of the 1950s is revived as explanation. When public sector enterprises falter or are selectively privatised, Nehruvian statism is blamed — even as many PSUs continue to underwrite dividends, disinvestment revenues, fiscal buffers and strategic leverage.

History becomes malleable. Accountability remains diffuse, obscured by selective memory and rhetorical convenience. The Vande Mataram controversy illustrated how easily the past can be repurposed. A century-old cultural dispute offers little guidance for contemporary policy, while carrying avoidable social risk.

This impulse extends into policy design as well. Congress spokesperson Supriya Shrinate’s critique has found resonance because it reflects an observable pattern. A number of flagship initiatives under the current government closely resemble earlier programmes — sometimes improved, sometimes simply repackaged.

Food security schemes, insurance coverage, housing missions and financial inclusion drives often rest on inherited frameworks. Continuity is not a defect; in many cases, it is sensible governance. What erodes credibility is presenting rebranding as reinvention. Change the prefix. Change the logo. Claim transformation.

The fixation on renaming extends beyond schemes. Cities, roads, railway stations and institutions are routinely rechristened. Symbols shift quickly. Structural constraints endure.

Employment creation, MSME resilience, judicial pendency, education quality and healthcare affordability require sustained institutional effort. Distractions — whether rooted in historical grievance or partisan theatre — do little to advance public welfare. The costs of such drift are ultimately shared by supporters and critics alike.

Here lies the central irony. In attempting to distance itself from Nehru’s legacy, the ruling establishment cannot stop invoking him. The Nehru jacket, once a sartorial relic, has evolved into a metaphor for continued political reliance on the past. When delivery is questioned, history tightens into a constraint. It serves as a taunt, but also as a warning.

None of this denies that Jawaharlal Nehru made mistakes. He did. So did Indira Gandhi. So did Rajiv Gandhi. But no prime minister, past or present, has been infallible; Narendra Modi, Morarji Desai and Atal Bihari Vajpayee were no exceptions. Acknowledging historical error need not weaken the present; it can strengthen it.

Effective leadership is distinguished not by how often it blames predecessors, but by how decisively it corrects course. That can be done without rhetorical mudslinging that stains even borrowed garments.

There is also an unavoidable generational reality. India’s median age is under thirty. Most young voters have no lived memory of the Nehru-Gandhi years. Their expectations are shaped less by ideology than by employment prospects, prices and relief from constant financial pressure. In the name of educating them about history, care must be taken not to mislead or entrench permanent suspicion.

For them, Nehru is neither villain nor saviour. He is a chapter. And chapters are meant to lead somewhere.

Notably, the taunt has now entered the Congress lexicon as well, almost in confirmation of Newton’s law that action provokes reaction. The rhetorical loop sustains itself — precisely why Priyanka Gandhi’s intervention matters. Debate history, she suggests, but do not take refuge in it. Deliver in the present. Account honestly for promises made and promises fulfilled.

This is where unease begins. Where is the publicly available audit of manifesto commitments? Where is the candid acknowledgment of policies that have underperformed? Where is the readiness to recalibrate without summoning long-departed leaders?

Governance cannot function as a permanent campaign. History cannot serve as a permanent alibi.

A final observation, offered without rancour. If the Nehru-Gandhi era committed errors, the lesson is not to invert them, but to avoid repeating them. Centralisation cannot replace consultation, just as institutional erosion cannot masquerade as reform. Optics may capture attention; outcomes alone secure trust. Power, however entrenched, must never substitute accountability.

History is unforgiving to those who fail to learn from it.

India’s economy, institutions and global standing now require seriousness beyond rhetorical hauntings and political provocation.

The haunt has lingered long enough.The taunt has lost its edge.

And now, to borrow an old phrase, it is time for all good men to come to the aid of their country.

(The columnist is a Mumbai-based author and independent media veteran, running websites and a YouTube channel known for his thought-provoking messaging.)